As the pernicious COVID-19 virus continues to work its way around the world, the voices of the poorest and most marginalised in society have largely been missing from the mainstream media coverage.

The Refugee Journalism Project contacted three journalists who live in Dzaleka Refugee Camp in Malawi – one of the poorest countries in the world – and invited them to help tell the grassroots story of how this global pandemic is affecting those living on the fringes.

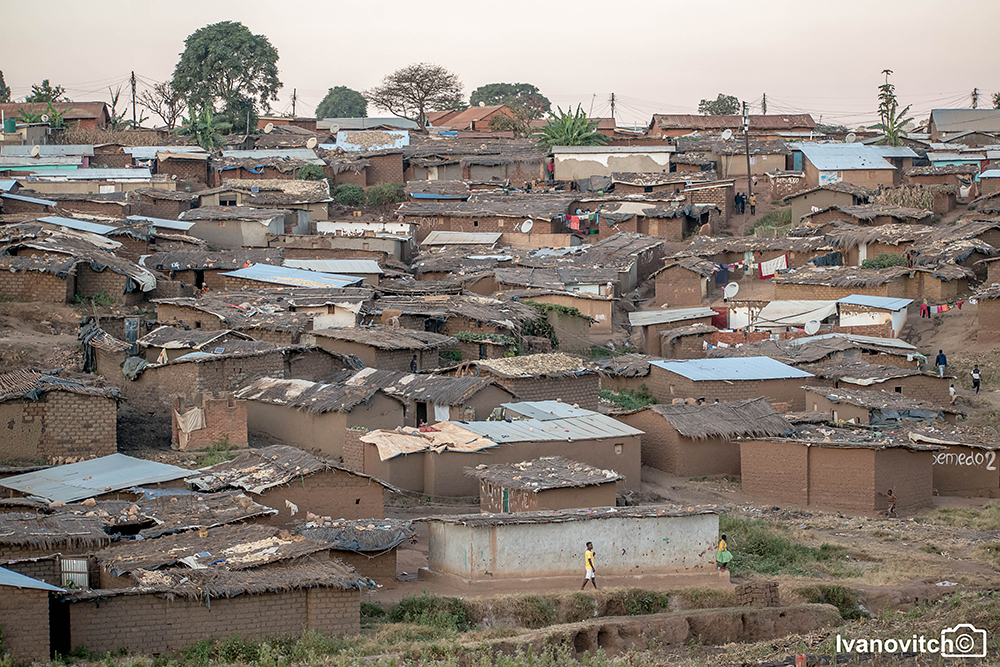

“Dzaleka” means “I will never try again”. Once a high-security prison, it is now the only permanent refugee camp in Malawi, south-east Africa. Located 50 km from Lilongwe the country’s capital, the camp houses over 44,000 people who came to Malawi in order to flee the instability and political upheavals of their home countries.

Living conditions in Dzaleka are precarious: the camp, originally built to house 10,000 people, is stretched at 300% of its capacity.

Despite being politically stable, the Malawian economy is struggling. It relies heavily on the export of farmed goods – an industry that has been shaken by declining world prices and environmental pressures.

According to the Malawian charity There Is Hope, the population of about 18 million is one of the fastest-growing in the world, with 45.1% of the population fifteen and under. Life expectancy stands at roughly 57 years for women and 60 years for men. More than half of the population lives on less than $1 a day.

Still, the country remains a safe haven for many refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Burundi, Rwanda, and Somalia amongst others, mainly fleeing from armed violence and, in case of the DRC, a historically significant Ebola outbreak.

Dzaleka opened as a refugee camp in 1994 and is jointly run by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the World Food Programme (WFP). Other organisations such as the Jesuit Refugee Services (JRS) and Plan International Malawi (PIM) operate programmes to provide help to the inhabitants.

In April 2020 when it became clear that the pandemic was spreading unabated throughout the world, we asked multimedia journalists Leopold Kalala Heritier, Godeline Ndonji and Ivanovitch Ingabire, who live in Dzaleka, to find out what impact it was having within the camp.

When they started gathering their interviews, a lockdown was announced as the virus had hit Malawi, but no cases at the camp had been reported.

At the time of writing, the government’s lockdown plans have been put on hold indefinitely by the Malawian high court. However the fear that COVID-19 will eventually shut people off from access to food, water or help still exists.

From talking to the journalists and going through the material they produced, the overwhelming feeling is one of powerlessness and resignation. Many say that they are failing to feed their families and suffering from hunger.

As Malawian law prevents refugees and asylum seekers from seeking employment, the camp’s population is mostly unable to earn a living. There are two ways residents can earn extra money: to start a business if they are lucky to have the money to invest, or by working as a volunteer in return for a stipend. This leaves the majority of Dzaleka’s population highly dependent on charities. With the virus affecting the entire globe, some inhabitants worry that the donors and organisations will turn away from Dzaleka, leaving the camp without its life-sustaining resources.

Hunger has always been a problem in Dzaleka. It has only got more dramatic when monthly rations were halved recently. The rationing has been cut down to 0.75 kg of pulses, 0.38 kg of food oil and roughly $ 3.3 per person. In total, the monthly hand-out food now contains about 6,000 calories, less than an average adult needs for three days.

For the supply that they have left on their shelves, store owners have increased prices.

To provide enough food for one person per month, our reporter Leopold tells us that he would need $ 50. But even if he had the money, there is the problem of where to get it?

Whilst supermarkets are still open, leaving the camp and shopping outside has been banned. Many refugees used to rely on this – but now they are forced to depend on food banks even more.

Access to clean water is also limited. As of February 2019, Dzaleka residents are only able to access roughly seven litres of water per day, distributed via 38 hand pumps and 15 water kiosks. To put this into perspective: an eight-minute shower uses 62 litres of water.

Despite the official guideline being “keep your distance”, people still attend gatherings. Churches continue to be a significant part of the social life of Dzaleka. The service, along side practising one’s faith, also provides an important channel in reaching the camp’s population.

Pastors emphasise the need for hand-washing and social distancing. In a climate where many of the population rely on news forwarded by online groups, coming together at church might play a crucial role in preventing the spread.

In an attempt to fight misinformation, the camp’s own media organisations are working to show the dangers of COVID-19. By sourcing information on the situation around the world, they hope they will make the camp’s community adhere to the recommended measures to avoid the death toll reaching the heights of Europe or the USA.

Strict adherence to prevention tactics is crucial: should the virus hit the camp, it is unclear how effectively its spread can be prevented.

Improvised sinks for hand-washing have been implemented but many residents use their water rations for cooking, washing and cleaning, skipping the extra hand-washing. Medical services, despite being there, have always been sparse, as well as access to drugs.

Should the virus hit the camp, it is unclear how effectively its spread can be prevented.

Testing procedures for COVID-19 are chaotic and new arrivals are greeted with a general suspicion over whether they are bringing in the virus. New arrivals, for their part, are afraid of the 14-day isolation that requires them to spend the time in tents with strangers.

For refugees, having fled violence and persecution, this requirement is an additional burden. After all, not being able to seek shelter in the anonymity of the general camp might arise the fear of being tracked down by violent gangs, as our reporter on the ground Godeline told us.

In this article, we share the material that the journalists collated, publishing, as far as possible, the verbatim accounts. The interviewees, which include radio producers, pastors, community leaders and expectant mothers, have the opportunity to tell their own stories of what it means to be vulnerable in a country that struggles to take care of its own residents.

They also reveal how it feels when you are not prioritised for global help – living in fear for your life, your health and your sanity each and every day.

Sada Bakari arrived in Dzaleka from the DRC in 2018. She is a single mother of one, and is expecting her second child. She is an asylum seeker and lives in the temporary transit area until her status is granted and space is found to house her in the main camp area.

“We are living in congestion. We are so many people. My worry is the way we are living. There are many families here. As you see bedrooms there, everyone has his family and has children and they are singles. Like singles, they have one bedroom, where 10 or 5 singles sleep. Now tell me that respiration has not gone to someone else?

“We do clean but external people come and mess up. We don’t have access to that thing of covering the nose when cleaning because when swiping, one inhales those bad smells and that is how the disease comes.

“Concerning the access to health care here in the camp, we are not helped especially during this current situation. Like (they) have stopped vaccinating children, and when you get sick they don’t receive you. They only receive pregnant women.

“To be frank, life in the camp is very tough. No one will help you when they get something and leaving one’s children which is not possible because everyone is fighting for their kids. Everyone goes out there doing their best in order to get something for their kids to eat. The one who has a good heart sometimes helps those who don’t have (anything).”

Kibinga Malipo is an asylum seeker originally from the DRC. He arrived in Dzaleka in 2019. He is unemployed and lives in the transit area.

“The way we hear about corona is that it is a very dangerous disease that doesn’t delay to kill people. If someone is positive, they have a few days to live.

“Since the day we heard about corona, we are living in fear because we are living in a transit where we are overcrowded.

“Us living in the transit area are at high risk of getting contaminated because we are like breathing each other’s air as we are living in an open area. Therefore, we are asking camp authorities to help us find another place (other) than the transit because it will help us avoid the contamination.

“Since this outbreak, we heard that new arrivals are being isolated in tents for 14 days. After being treated and tested for 14 days it is when they’re allowed to go in the camp.

“It is good to isolate a new arrival for them to be tested for our safety because if they come straight here in the transit, we will be affected.

“I don’t have access to any media because I don’t even have a radio. And nowhere to get information thus I get the news from people.

“When we get sick, if we go to the camp hospital, we get treated when there are drugs and if not, we are often given Panadol (a standard pain killer containing paracetamol).

“We only have one borehole in our area. So, for us to get water, we wake up at 2 am and sometimes spend the whole day without getting water.

“Since this pandemic started, we never get access to any sanitizer, soap not even a bucket.

We depend on food banks nothing else. And if there is a delay in food distribution, one can spend even a week without eating.

“We depend on food banks, nothing else. And if there is a delay in food distribution, one can spend even a week without eating.

“The way we help each other here in transit is that if someone gets something, (you) can’t eat without giving to the kid. We rely on the little thing that we get because if you wish to get a lot where are you going to get it? We are just thankful to God for the little things that we get.”

Niyongiza Dafroza is an asylum seeker from Burundi. She arrived at the Dzaleka camp in April this year.

“When I arrived at the camp, they told us to pass through testing of corona. They told us that we will stay in isolation for 14 days as we will be going through the test because we have to be tested on a daily basis. We are being tested every day in the afternoon using the non-contact forehead infrared thermometer.

“We’re not well treated because some of us here cannot eat the food we are given because we are not used to it and it causes stomach problems to some of us.

“And during night we get cold because we are not used to this new weather, even the duvet cannot be helpful of coldness because we are sleeping on the floor of the tent and it gets cold as well.

“They have not yet told us what we shall be given or where we shall go. We’re just waiting for the 14 days to be over and know what will be next for us. We are afraid, mostly during the night, that people can do bad things to us.”

Musimwa Nigabo is a refugee from the DRC. She arrived in Dzaleka in 2011. She works as the Congolese deputy female leader. She lives with her two children and her husband.

“Life is hard in the camp because people are just staying at home which is increasing theft in the camp.

“When someone has flu at this moment, he is afraid to go to the hospital to avoid being taken as COVID-19 infected.

“As a community leader, I have no choice to work with people coming from different places. I’m in contact with some new arrivals every time which means that I’m at risk, but I just put my faith in God.

“At this time food prices increased since people are selling the only food which remained in the store before the lockdown. We try to find another way to survive apart from the food we receive.

“There is no solidarity in the camp because people don’t trust each other – not only fearing corona but also poison. But mostly churches try to sensitise people to live in solidarity.

“Most people get information about the virus from their religious leaders. They mostly teach believers how to protect themselves from this deadly disease. They insist on frequent hand washing and social distance.”

“I think we better die with corona rather than being in lockdown because we have to access basic services for survival such as food, water, maize mill, market, etc.”

Mike Mageza is from the DRC. He is 24 Years old and arrived in Dzaleka 12 years ago. He owns a convenience and clothes’ accessories shop in the camp.

“Here in the camp we are thousands of people in the camp. Everybody has to get access to water. I can’t say we have access to water. Because you can find that on one pump, we use pumps for water, there may be maybe fifty people fetching water. So, let me get to the point of washing hands.

‘In this camp as I said before one pump gets 50 people, we form lines in front of the pumps. If I fetch two buckets of water, and me and my family are five, we have to bath, we have to eat, so I don’t think it’s that necessary to wash my hands because I will use that water.

‘Covering the face, first thing is that I don’t know where to get a free mask right now. I heard people are selling it for MWK500. For example, like me I earn MWK1000, I can’t afford to buy four masks for my family, I can’t afford it, you see.

‘I can’t lie, this camp is a multi-cultural camp we have people from different cultures and different backgrounds so it’s very very difficult to interact, not easy. We find that people from different nations segregate themselves and talk to themselves.

If I fetch two buckets of water, and me and my family are five, we have to bath, we have to eat, so I don’t think it’s that necessary to wash my hands because I will use that water.

‘We are not sure of what is really going on because we heard rumours like in Malawi there are some cases 17 cases of corona so there is being announced that there would be a lockdown but it’s confusing everybody in camp. I don’t feel safe. In the camp, everybody is dangerous because they might infect people. I’m doubting it, I’m really doubting it, that there will be a lockdown in the camp.”

Listen to Mike Mageze’s audio interview:

Safari Buzige Pascal is a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). He arrived in Dzaleka in 2015. He is a 63-year old father of two. He lives with his mother, his wife, their two children and his three grandchildren.

“There is hunger in the camp because food has been cut in half ration which is not enough. Eating has become tough.

‘We used to pay Malawi Kwacha (MWK)1000 ($1.20) when going to the capital city Lilongwe from Dzaleka. Now we are paying MWK 4000 ($6) and food has become expensive. Normally a person has to eat twice a day, but we are struggling to eat even once.

‘People live in solidarity in the camp as some people do help others in need, with the little they could have. However, people don’t work. If we have a little job where we can get something that can help the family gain every month, we could help. We do help each other with the little something we get.

‘Almost everyone is afraid of the disease. No one is not afraid.”

Pastor Olivier is a refugee from the DRC. He is the head of the Emmanuel Full Gospel Church in Dzaleka.

“Personally, as the head of the church, I feel like it’s my responsibility, my task to understand how this disease spreads and how it contaminates people.

‘So, I found myself in the obligation to learn more and understand it deeply so that I can help other people or teach other people how to [protect] themselves.

‘I’m still wondering about the boreholes, how people gather at the boreholes, where you find many people gathered because they have come to fetch water. What should be done to avoid contaminating each other once the disease is here?

‘Solidarity is something that began long ago in this camp, people are able to help each other. That means if you have a neighbour who is missing something it is really easy for that neighbour to ask and [get] help but you cannot give when you don’t have.

‘I think if the government will decide to isolate people that will be a very difficult and horrific time because people here depend on what they receive, on reliefs they receive.

‘Now, if they are to stay at home yet they have not met their basic needs, it’s gonna be really hard for them and that is compared to killing them. It’s like the government is killing them by deciding that, because, mostly, here people depend on others.

‘And now if you’re to isolate them, that’s killing them even before the disease itself comes to kill.

‘They should continue sensitising people about the spread of the disease and how people can protect themselves but most importantly, people should put their trust in God.”

Niramana Claudine is from Rwanda. She arrived in Dzaleka in 2002. The 27-year old mother of three lives in her mother’s house with five siblings and her children.

“The atmosphere is not good because people are struggling to find the food ration and the money we are receiving is not enough. Can you imagine someone leaving with MWK 2275 ($3.3) for the whole month?

‘I used to wash clothes for people and earn money that was helping in supporting my family but since this corona came, I was stopped from working while I had a big credit from shops of some food items that I have been taking, thinking that I would pay when I get the stipend. But now I don’t know what to do.

I’m afraid of the disease but mostly of dying from hunger.

‘I’m afraid of the disease but mostly of dying from hunger. I don’t get helped by anyone in the camp. I’m not safe, life is hard and we are thinking too much to survive.”

Raphael M. Ndabaga is a refugee from DRC. He is the director of the camp’s community radio station Yetu, and the founder and spokesperson of the Musicians’ Association of Dzaleka. He teaches economics at Arrupe Learning Centre. He is also currently studying for a diploma in Liberal Studies. He lives with his wife and two children.

“Really, you know with fake news, people are not aware of the information itself. So the facts that this pandemic is real, it is killing.

“When you try to watch news, when you see what is happening in USA today, if you see what is happening in the UK, what happened in China, in France, in other countries, you believe that coronavirus is real.

‘Even here in Malawi, something is happening even though cases are not reported each and every day, but we have reported some cases of death so this pandemic is real.

‘And some people are receiving the message and accept that it is real, but others reject the fact, they say coronavirus has been politicised.

‘At the community radio, as a media house, our news, each and every day in this specific period, is very centred on the corona pandemic.

Some people are receiving the message and accept that it is real, but others reject the fact, they say coronavirus has been politicised.

‘So the news bulletin that we are reading daily, 99% of our topics of those specific news are based on the coronavirus pandemic. Because sometimes other people might say Corona is not real. But when you read our news, we show how Corona is affecting the world.

‘Then we show our own community that it is what is happening in other countries so for us, we don’t have to wait until we reach at this stage losing more than 10,000 people, more than 1,000 people, more than 100 people per day. We don’t have to reach this far.

‘We have to take responsibility for respecting the prevention measures and try to emphasise to others that we have to maintain this.

‘And I’m glad that my own community of Dzaleka has never recorded even a single positive case of Coronavirus. And we are trying to make it until the end of this pandemic, our wish is to stay safe during this period because we are already vulnerable, we don’t have anything. We are refugees.

‘So if we are hit again with this pandemic it means we’ll be recording even 10,000s of people per day or 1,000 people dying per day. Our wish is to tell people what is happening based on this pandemic. So that everyone should be aware that this pandemic is real and we have to protect ourselves and protect others.”

Omari from the DRC is 42 years old. He arrived in the camp in 2012. He is a married father of seven children. He is a businessman who owns a shop for phones and mobile accessories in the camp.

“The atmosphere is not good here in the camp because life is hard in here. I have no worry about corona but I’m much worried about life because getting food is becoming an issue here in the camp.

‘I have not received any sanitizer or face mask or soap but everywhere where I pass there is hands washing water. I depend on food banks but sometimes it delays and I do fight as a man to get something for my family.

I have no worry about corona but I’m much worried about life because getting food is becoming an issue here in the camp.

‘We live in solidarity as Africans. If I get something I share with others and when they also get something, they also share with us.

‘Before corona, everything was good here in the camp but since this outbreak, we don’t trust each other thinking that they have corona and that is why when I look at you, I am afraid because I think you have corona and when you look at me you are also afraid thinking that I am infected.

“Dzaleka used to be a good place, this corona has brought panic.”

Butoyi Fidele is the male leader of the Burundian community in Dzaleka.

“Here in the camp, there is an issue of food security. Refugees don’t eat properly, as they wish, and the reason is that donors may get tired of helping this refugee camp because this camp exists since 1994 where the number of refugees increased from 500 to 50.000.

“The camp is small with a lot of people. This high number of refugees causes an issue on food distribution; it takes some days to donate food to all refugees.

“Before, it wasn’t like this. Before, we were receiving food like beans, maize, oil, sugar, porridge flour, soaps and more stuff, as basic needs but nowadays WFP removed maize and exchanged it to money.

This high number of refugees causes an issue on food distribution; it takes some days to donate food to all refugees.

“They are on the beginning of cash money distribution from the bank, but it takes time to receive it because of network system from the bank failed sometimes and all this disturbs the life of a refugee.

“Everyone here now is aware about coronavirus from the news or relatives that people are dying in other countries.

“Psychologically it made them to be more cautious by washing hands most of the time and when you walk around you see buckets everywhere where more people meet meaning that they understood the message from the government’s campaign that of taking precautionary measures against this pandemic.”

Yousuf Abdullayah is from Somalia and is 20 years old. He arrived in Dzaleka in 2010. He is a student in secondary school and a poet.

“[The atmosphere] has been very hard because we have been running up and down for school and some other activities but now it has been very hard because COVID-19 has blocked every way of earning a living and any education.

“We’re not really feeling safe just because this pandemic is very scary. The only thing I’m worried about is that we don’t really know when we are going back to school because education is the key to success and we all know but as the more we stay at home the more we lose the skills we’ve been gaining for the past years we have been at school.

We’re not really feeling safe just because this pandemic is very scary

“I don’t think [the lockdown] will happen because we have all the social activities in the camp for us to earn a living, it’s always outside. We are not modernised. We are not like the western countries.

“In western countries, if you want to buy something, it’s always in the house. We buy things outside and do some activities so we earn a living outside the house.

“But now if this lockdown will happen, I don’t think us refugees will survive with this, or even Malawi. It’s one of the poorest countries in the world.

“Isolation will be very hard because my family depends on me in terms of the work that I do to help the family. The whole day I was at the farm so if I’d be isolated from my own family, the breadwinner in the family, will be a very big cut which will create a very big problem in my family.

“It’s very, very hard for new arrivals because people be afraid if you might have COVID-19 so you will be isolated, and isolation is one of the violations of rights. So, once you are isolated you feel like you are less human.”

Listen to Yousef Abdullayah’s interview audio:

Raphael Raymond is from the DRC. He is 27 years old and arrived in Dzaleka in 2009. He works as a teacher.

“Since the discovery of the COVID-19 started, people are so poor. The community will suffer, most of us we are going to die, because since this disease started, here in the camp many activities are stopped.

“Before I was more safer. Right now, most of us under custody, we have nowhere to go and we are not allowed to move outside of this camp.

The community will suffer, most of us we are going to die, because since this disease started, here in the camp many activities are stopped.

“[There is no unemployment support] during this time not because everyone is seeking for a job. Many jobs have been closed due to this problem of the epidemic, which we are facing, so is not easy to get something to really keep any opportunity to start working in any place and if I lost mine, I don’t have a supporting network.

“I’m so afraid of isolation, if you are isolated you have to be placed somewhere in a room, the room can’t ever give you money. So, if I’m isolated is not easy to find the oil for a living, to find some materials, to find water and even to earn any money. It’s not easy for me to keep up.”

To stay up-to-date with the developments in Malawi, the UN publishes weekly updates here.

To find out more about Dzaleka Refugee Camp, have a look at this fact sheet.

Multimedia Journalists (Malawi)

Godeline Ndonji arrived in the camp in 2011, when she was 14 years old. She is currently studying towards a management degree at Southern New Hampshire University through the global education movement (SNHU-GEM) and volunteering with the Jesuit Refugee Service as an operations assistant. Her nickname is La Perle, a testament to her character that she describes as loyal, humble and hard-working. She gathered video, audio and written interviews and background research in Dzaleka for this article. @Chrisvannie1, @perlechrisvanniela

Leopold Kalala Heritier is 24 years old and arrived in the camp four years ago. Whilst he did not speak English when he arrived, after two years of dedicated study, he now presents the news at the community radio and is working towards launching a TV station in the camp. He is also working as a voluntary interpreter with the UNHCR Malawi. For this article, he gathered audio and written interviews as well as background information. @mckalalathehost

Ivanovitch Ingabire is a filmmaker and photographer from Burundi. After arriving in Dzaleka, he constantly evolved his skills in both fields and now uses his camera to document his life in the camp – the joyful and the tearful moments. He provided visuals of the camp and our interviewees for this article. @ivanovitch_photography @tel_us_agency, Ivanovitch Photography

Researcher and Journalist (Germany)

Hanna Linnéa Mödder works as a digital journalist with the Refugee Journalism Project. She is a BA Hons Journalism student at London College of Communication and due to graduate in 2022. Her interest in immigration and human rights matters was sparked when she volunteered at a German refugee camp. Hanna was responsible for the research and written content of this article. @hannamoedder , @hannamoedder

Editor (UK)

Veronica Otero is a visual journalist and documentary photographer. She is the project coordinator at the Refugee Journalism Project. For this article, she curated and edited the multimedia content and was in charge of communication management with the reporters in Dzaleka. www.veronicaotero.uk, @veronicaoterophotography