By Hilal Seven

If there is anything more difficult than being a refugee, it is being a gay refugee. The story of Rosida Koyuncu is exactly like that. In fact, it is not only his gay identity that makes his story challenging, but all his other identities added up to his struggle. As it is both Refugee and Pride Week this month, I talked to Rosida about his journey from Turkey to Europe.

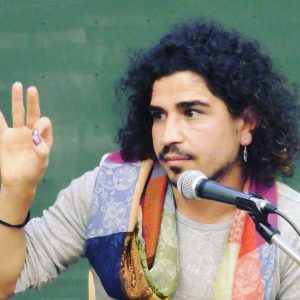

Rosida has been living in Geneva, Switzerland for three years, studying cinema at an arts school. He has been writing on platforms like KaosGL and Kedistan for over five years. He also performs different types of performances and participates in events. Currently, he is mostly working on his film projects.

How did your journey begin?

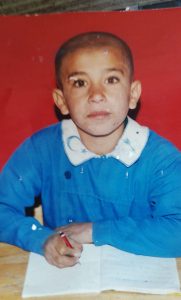

I was born in 1988 in a village in Bismil Diyarbakır. We made our first immigration in 1993 when our village was burned down along with five thousand others, all at the hands of the government of the time. Our house was burned when I was 5 years old after which we had to migrate to the city center. After moving to Diyarbakır, traumas continued.

As you know this well, it is unusual for a person who is born in Kurdistan not knowing that he is Kurdish or growing without politicization. For example, the language issue. When I went to school, I did not speak Turkish. We had a teacher, she failed the whole class in the first grade because none of us knew Turkish. She was a woman with a mini skirt and nail polish. Think about it, you’re going to a class in China, they speak to you in Chinese and you don’t understand anything. You are simply shocked and then it’s a big trauma. Then you start questioning and say ‘Who am I?’, ‘What am I?’, ‘Why do we learn another language?’, ‘Why can we not use the same language that we use to speak with our mother here?’. And I was coming from a political family, naturally I always had politics in my life.

When I was a kid, my father was in prison and we were going to visit him. Apart from that, there was a lot of confusion, and the fact that soldiers are coming to your village constantly makes you question a lot of things. Why are these soldiers coming to our village all the time? For example, I made a short 10-minute movie called Recep Avareş Rosida. I say this at the beginning of that movie. When I was 5 years old, my mother sitting in front of our house burning in the village is crying, I go to her and ask her, “Why are you crying, why is our house burning?” My mom doesn’t answer me, but she keeps singing and crying. Actually, my mom laments there.

Of course, there is another thing that all these events have brought, you see? Imagine that these are left in the memory of a young child. How should that child not be politicized when he grows up? Another is that I have a disadvantage because of my gender identity, especially in such a geography, I don’t need to tell you, you know how hard it is to be different. When you ask yourself Who am I? or What I am?, you don’t find anyone to help you figure out. And you think that you’re not normal, you’re sick.

When was the first time you realized that you are different?

I was young and I was a member of a traditional dance group. And I realized that I had certain feelings for a boy in our group. We never verbalized it, but we were being pulled towards each other. But when we finally talked about it all the magic was gone. In essence, you are fighting against yourself, in pursuit of understanding what it is. As an example to the results of such unsolved self-conflict is suicide which many had ended up committing. After coming to Istanbul in my own conflict process, I came to a more comfortable point. I didn’t know any gay or lesbian terminology back then due to limited access to information. You learn when you meet the internet. For example, the common word of all the lubunas is ‘there was me and only Zeki Müren’ (Zeki Müren was a very famous gay singer in Turkey). Your awareness increases as you learn, and you come to know there are other people like you. Nevertheless, there were still stages that I could not accept myself. I couldn’t even share my feelings with my mom.

Did you speak to anyone from your family?

Not really, because you are in a heterosexist world where a family consists of a father, a mother and their children which leaves you as an outsider to that world. After all, I come from both a feudal and a masculine society, and it is not easy to fight for yourself in such a society. My biggest conflict happened with myself.

For the first time I was able to speak to my sister clearly, when she realised how I was suffering.

One night I was crying again, begging God: “Please god, correct me and take these feelings that I have towards men away from me or turn me into a heterosexual woman”. My sister heard me cry and asked me why I was crying. I said, my soul and my body don’t match. Then my sister’s words became a key to me, she said, ‘If you are crying, this is you, don’t cry because you are yourself’. Meanwhile, I was taken to the doctors, I was told that I was sick. My therapist said that this was not a disease, but a sexual identity. I was almost 25 years old when I completely accepted myself.

Please god, correct me and take these feelings that I have towards men away from me or turn me into a heterosexual woman.

Why are you in Switzerland?

I stayed in prison for two years in Turkey – I was arrested for being a member of an armed organization. I was because of the reality of coming from Kurdistan and being in the Kurdish political movement and dealing with politics. I was sentenced to prison for six years and three months. And after two years of imprisonment I came here as a guest of a festival and took refuge in order to save myself from going into prison again.

I stayed in prison for two years in Turkey – I was arrested for being a member of an armed organization. I was because of the reality of coming from Kurdistan and being in the Kurdish political movement and dealing with politics. I was sentenced to prison for six years and three months. And after two years of imprisonment I came here as a guest of a festival and took refuge in order to save myself from going into prison again.

I have been living in Geneva for three years, I am here as a political refugee. It actually happened when I started discovering myself in this process. I was taken to the doctors before, I was told that I was sick. My therapist said that this was not a disease, but a sexual identity. But this dealing with self-conflict has never been easy. I was almost 25 years old when I fully accepted myself.

How did you start writing?

I actually started writing when I was little. I wrote a sketch called ‘Mamoste ez tirkî nizanim’ which means ‘Teacher, I don’t speak Turkish’ and some short stories. Writing is like vomiting for me. I’m throwing up what’s inside. Whatever touches me and makes me think, I take it out from deep within and write it down. Think about it, I always say to myself, there is no place for you in this world. And you believe it. I always write my own inner conflict, my testimonies, in fact I vomited them in a sense. On July 2, 2012, a child named Roşin Çiçek was killed in Diyarbakir by her father and uncles, and nobody claimed her funeral, neither lawmakers nor officials. At that time, this event made me think a lot and I started thinking about what I should do. Since then I have been writing for different platforms and I published a book called Voltaçark.

I am not actually a journalist, I report unknown stories, I carry them. Sometimes I vomit them. Something like this I did in the cinema.

What would you say to the 15-year-old Rosida (Recep) if you had a chance to speak to him now?

I think I would tell him, calm down, you’re going to have your place in this world just like everyone else. I know you’re looking for yourself, but be sure you’ll find yourself. You must live yourself, or you cannot be happy when you live with someone else. I am 31 years old now and I think I was on fire when I was 15 years old. I was distributing newspapers back then. I had a t-shirt that said ‘aşitî’, and whenever I wore it, I would say anything in my mind when I walked passed a police station; could the cops stop me because of my t-shirt? Where was I then and where am I now? When I was 15, I was Recep, now I am Rosida. As a matter of fact, I wrote a book called Voltaçark where I talk about Recep. A sentence from this book is: ‘They call me sick but nowhere does it hurt’.

What is the hardest part of living as a refugee?

I am very sorry for the deteriorating situation in Turkey. I wonder if one day I will return to Turkey. I feel a lot sadness when I see the photos. For example, my biggest fear in this corona process was to not be able to go see them if something happened to my mother and father. But on the other hand, my family is happy that I am here, because I won’t be in prison again. And I’m learning a new language, I’m building a new life, and that’s a good thing.

Who are you inspired by?

Actually, James Baldwin is an important figure for me. There is even a documentary called ‘I am not your negro’ and it has an important story. He is a black gay man but he tells them I am not your black. I am actually like the Kurdish black. I feel the same thing. The point I aimed to myself was this; We need to explain this situation to the Kurdistan society, and I know it is not easy.

For example, I define myself as queer because I don’t define myself by masculinity codes. I think the Kurds also need to see and recognize these habitats. We are not only in the capitalist cities of the world, we are also in their villages. That was the main reason I wanted to shoot Kurnaqiz. Because a Kurdish child in Kurdistan wears a women’s dress, it describes the internal conflicts and exclusion he experiences via the metaphor of dress. It was a short film to describe the society.

What are the things that ignites hope and motivation in you?

I know that life is very short, especially after a personal experience when I almost died from drowning in the water when I was swimming in a river here in Geneva. When I came to myself I said, life is short and you have to live it to the fullest. That said, all my experiences are sources for my motivation, and for my life energy.

Do you have any new projects?

Actually, I never made a program or plan. I had no plans to write books when I got out of prison, but I had to explain what I had experienced some way. When I did start writing after all, it was not with the intention to be a journalist and make money out of it. From my own eyes, I told all my experiences.

In fact, people may not like my writings, but this makes me more whips (laughs). For example, I do not know what to do after 5 years, but I would like to do gender workshops in Rojava (Northern Syria) and work on gender workshops by cinema.

I now have a more relaxed life and I can live myself, but one fact is that many refugees are in a very difficult situation and the housing conditions are very bad.

If a friend I knew hadn’t helped, I would have stayed in underground camps like many people and you would never want to be there. There are people I know here that have been in camps for years and all living spaces are camps.

To be honest, I would like to express that, since we are in Refugee Week, let me say this, Europeans are responsible for the lives of all refugees who die in the Mediterranean Sea and the Aegean Sea. Because they don’t open the doors, they cause those people to pass through those waters.

For example, being a refugee and a gay and staying in the camp is not easy. In Europe, romance is not rosy. One of the things I want most is to be able to translate my book into languages like English and French. And making queer cinema. Who knows, maybe I will come to London sometime!

Images supplied by interviewee.